On my second day in the Ambavalao area, I ask my guide Adrian if we can visit the Sakaviro forest.

Located just 5 km down a bumpy dirt road and practically spitting distance from the popular Anja Reserve, the Sakaviro Forest offers visitors a new perspective on the region, and the chance to support a village and show them the financial benefits of preserving their forest.

En route, we pass villagers who seem stunned to see us and our 4×4, but we push on. We arrive at the office in a clearing, with the doors and windows closed and no one in sight. Adrian and I continue on foot to the village to ask permission to see the forest.

Upon arrival, dozens of men, women, and children greet us, with their wide eyes and smiles seeming to ask, “Who is this vazaha and why is she here?”.

Adrian explains in Betsileo (the Malagasy dialect of this region) that we have come to see their forest and want to try to see lemurs.

Three men from the village volunteer to show us the forest.

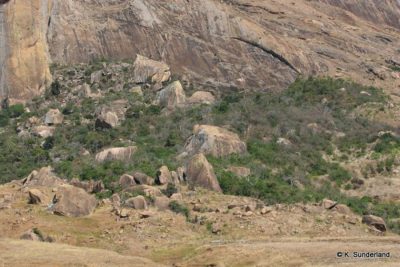

We walk across fields of tall, brown grass toward a large rock formation. To our left is a zebu herder, moving the cattle along. While the village guides do not speak English and only very little French, Adrian translates for me. With the communication difficulties, I know very little about what we would see, where we are going, and how long this hike will take. But, I am humbled to be here in a forest rarely seen by tourists.

The guides tell me that they once brought a Canadian student and an American into the forest. Could one of these legendary visitors be Tara Clarke from Lemur Love? I wonder if this is the last time they had any visitors — in 2012, four years ago.

After walking through tall grass for a while, we arrive at a sacred meeting place, where the village holds large meetings to ask the ancestors for help and make decisions. I wonder if they are asking anything right now: for us to see lemurs, for more visitors to come see their forest, or for more plentiful resources?

Spotting Ring-Tailed Lemurs

We enter a rockier area with some trees and begin to ascend. One of the village guides points to a tree that bares fruit that the lemurs eat. Not long after, he points up and we see two ring-tailed lemurs. I start to photograph them, and immediately they make an alarm call. One jumps away and the other soon follows. I am happy to know that at least two ring-tailed lemurs remain here, and hope there are others among the rocks and trees. I also wonder if this community hunts the ring-tails when food is scarce.

For now, I can do my part to let them know through my presence and my money that the ring-tails, their village, and their forest are valued.

Visiting A Historic Cave

We continue on up the mountain, and arrive at a cave. The guides explain that this cave is where their people lived when they were hiding from the French. Though big for a hiding spot, it is amazing to imagine many families from the village huddled here in fear. They had constructed two rooms, with a rock barrier dividing them. The room on the left was where women made silk, and you can see the black ash on the ceiling where there had been cooking fires. Later, Adrian tells me there was a big fight in this area and many people died battling the French. I do not know how long they lived in this cave, but I am honored to have been shown such an important piece of their family history.

Seeing Remains of a Protestant Church

We continue walking up, and arrive at the top of a hill and a large rock overlooking the valley. The rock has “188” painted onto it. The guides tell me this is the remains of a Protestant church built in 1886 all the way up this mountain. British missionaries and local Malagasy built this church, but very little remains.

By this time, the guides are feeling proud and more comfortable around me. I get the feeling they will tell the story of this day for quite some time.

On the walk back through the tall grass, they find casava root, and our guides dig some out of the ground for a quick snack. One guide runs to the zebu herder to share the food. Adrian explains that that these herders can not carry rice or much food, so this is a very kind gesture.

Meeting with the Village President

When we arrive back at Zina’s car, he is chatting with the village President. The elders decide the cost for this hike is 5,000 ariary for the entrance and 5,000 per guide, so 20,000 in total.

I gladly give the money to the President and tell them that I will tell people to visit their forest, and I am honored that they showed me their cave and their land. I sign their guestbook, and the village President tells me I was the first visitor to the Sakaviro forest all year, in September.

On the drive back down the dirt road, Adrian plays traditional Betsileo music from his cell phone—the very lively zebu dance song. It was a perfect ending to the village visit and hike. I did not know what to expect, but when traveling in Madagascar, it can be these unexpected encounters that stay in your heart the longest.

About Tara Clarke’s Time in Sakaviro

From Tara Clarke:

“I do believe that when they mentioned the Canadian and American, that was me and my research assistant, Kristen Sunderland. We visited in 2012 right after they had become an official protected community reserve. It was very exciting because we were the very first non-Malagasy people to ever visit or conduct research at Sakaviro. I distinctly remember signing the guest book and having my name be on the first entry line! During this time I was wrapping up my dissertation data collection. I had been working at the Anja Community Reserve and in the Tsaranoro Valley.

My team and I spent three days at Sakaviro looking for lemurs and poop, which I was going to add to my sample collection and analysis to examine how fragmentation and isolation impacted RTLs’ genetic health. I wanted to get a census of this new area that I had not been aware of before, nor had anyone else to my knowledge. We met with the association’s president and worked with a couple of guides. Everyone was super friendly and accommodating and worked very hard to help us count the lemurs in this tiny, rocky (14.2 ha) forest fragment. Despite the lemurs not being habituated, we were successful in collecting fecal samples, and counted a total of 30 individuals.

All of the village members, the president of the association, and the guides we worked with expressed a deep commitment to the forest, the lemurs, and wanting to develop Sakaviro as a successful eco-tourist destination. I have been hoping to return ever since I left, and I hope I can make a visit in 2017!”

My Travel Details

- Driver: Zina, booked through Asisten Travel

- Guides in the Sakaviro Forest: Adrian from Anja Reserve, along with three villagers

- Where I Stayed near Anja: La Varangue Betsileo. This hotel is rather pricey at 110,000-130,000 ariary depending on room size, but the views are gorgeous and there is a swimming pool.

- Cost to Visit Sakaviro Forest: 5,000 ariary entrance fee + 5,000 ariary per guide, paid to village President