When I first heard that giant lemurs had once roamed the earth, I was fascinated and devasted.

Fascinated to learn that at one point in our planet’s history there had been at least 17 large-bodied species of lemur, the largest of which is estimated to have weighed 160 kg. But I was devastated because researchers think these giant lemurs may have been around as recently as 500 years ago. I had just missed them.

Today, there are 111 species and subspecies of lemur, which is heartening. That incredible diversity of species—from the bizarre aye-aye to the hilarious indri—is what drove me to Madagascar. I wanted to see lemurs in the wild before it was too late.

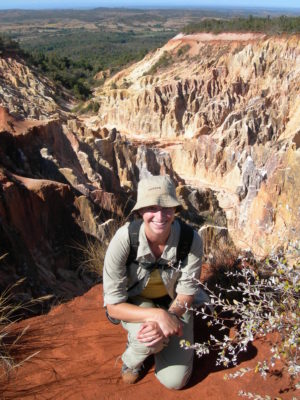

I visited Madagascar for the first time in 2006. I was 25 years old and going to study lemurs in their natural habitat for my PhD research at the University of Toronto. I wanted to explore the impact of the forest edge on how lemurs behaved, what they ate, and where they lived. I would spend three months there for my pilot research project, setting up a research site in the remote northwest of the country. I write about that journey in my memoir, Chasing Lemurs: My Journey into the Heart of Madagascar (Prometheus Books).

Before I left for that trip, I knew that lemurs were endangered mainly because of human-caused habitat loss and hunting. But in 2006, I was not fully aware of the extent of the crisis. That trip came before the 2018 announcement from the IUCN that a whopping 95% of lemur species are under threat of extinction.

In Kasijy Special Reserve, where I was heading for my PhD pilot research, I had the chance of seeing eight different species of lemur. Kasijy is in the remote northwest of Madagascar. My PhD supervisor, Shawn, would be with me for the first few weeks, and we would also be working with two Malagasy researchers from the University of Antananarivo. We spent months planning our expedition and no detail was too small. Shawn even went so far as to calculate how many kilograms of rice we would need per person on the team (anyone who has visited Madagascar can tell you how important rice is).

Credits: T. Steffens

To get to Kasijy, we would drive from the capital city of Madagascar, Antananarivo, to the nearest small village called Kandreho. From there, we would hike 18 miles over sandy and rocky terrain. When we arrived, we would camp in the bush, digging our own latrines and filtering our water from the river. How hard could it be?

Before I departed, even though I knew better, I pictured Madagascar as a country filled with lush, green forests, where lemurs were practically falling out of the trees. On my way into Kasijy, I was confronted by the reality. Madagascar had seen a great deal of habitat loss, with estimates that between the 1950s and 2000, it lost about 40% of its natural forest cover. Where I thought we might find ourselves driving through deep forests, we saw only rolling hills, hardly a tree in sight. I had imagined seeing my first wild lemur deep in the forest in a big tall tree, and never expected that my first would be a mouse lemur in a scrubby bush near a small village.

Despite our best laid plans, that trip into Kasijy spun out of our control. What we had anticipated would take three or four days ended up taking 12, and included food poisoning, throat infections, armed military men, gnarly backcountry roads, and challenging local politics.

Credits: T. Steffens

We did eventually make it to Kasijy, where there were lemurs at camp. But soon after our arrival, my supervisor had to depart, leaving me, the only woman on the trip, in charge of a team of Malagasy men. A few days in, in the middle of the night, I awoke to learn that one of the university students, Andry—the only other person there who spoke any English—had been struck down with malaria. I found myself leading a rescue mission involving dugouts and makeshift hammocks out of the wilds of Madagascar.

I tell the story of that harrowing journey in Chasing Lemurs. But the book is also a love letter to Madagascar—an incredible country that is, sadly, at risk. Even though that first trip did not go as planned, I have been drawn back to Madagascar over and over. In all, I have lived and worked there for 19 months. I have seen how habitat loss and hunting are impacting the lemurs. I have met and worked closely with Malagasy people, including many who live on less than two dollars a day.

Today, I volunteer for Planet Madagascar, a non-profit organization that is working to help people and lemurs. Although the challenges in Madagascar can feel insurmountable, I am encouraged to know that there are organizations out there—members of the Lemur Conservation Network—who are working toward the same goal: to conserve those 111 species of lemur for future generations.

Credits: T. Steffens

Buy Chasing Lemurs: My Journey into the Heart of Madagascar here!

Learn more about Planet Madagascar here.