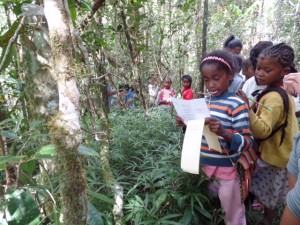

She is just beginning her PhD in Education at the University of Sussex, where Daniella came for an MA in International Education and Development in 2011. Since, PLAY began by finding a diversity of committed peers throughout Madagascar who are invested in promoting the agency of local communities. Since 2014, they have begun to explore channels to reconnect forest and rural spaces, through collaborative education developments.

In this 2015 conversation with Daniella, she tells us all about PLAY, what inspires her, and the challenges she has encountered along the way of developing a platform for rethinking sustainability in the island.

How Daniella Started PLAY

Where does education come in?

Daniella Rabino, the driver behind PLAY, Protecting Life through Active Youth, asked this as a study abroad student in 2007.

As an elementary education student, it seemed like education was left out as a central part of redefining relationships between state, NGO bodies, and local lives, to connect ideas across spaces.

I started realizing that these issues were big and the intersections between fields were not really addressed in a way that they could be … and I was in a privileged position to be able to help take that on.

During your trip, you noticed areas where there might be a possibility to bridge these disciplines. Can you tell me more about how you developed the concept of PLAY?

The old conservation language always talked about people in Madagascar, the rural poor, as destroying their future as though they’re committing ‘ecological suicide’, framing the majority of people as a problem to fix, rather than those who lose out from broken systems. And meeting teachers and children in different villages, I realized that most people wanted to know more about what they could do to protect their own lives, yet are invisible.

When teachers would ask me about how our rain forests were doing in New York, it put in perspective for me that those who most depend on the interconnections are left out of its directives for Madagascar.

Teachers came to me concerned about how their environments were changing and what it meant for their children – what could they do to prepare their children, as I was an undergraduate with so much support in learning to be a teacher. It seems fundamental to start with communities knowing why so many people care about their island. Yet, conservation and development efforts often overstep these systemic problems of including communities to lead in.

So many of the questions in conservation overlap with children.

In Madagascar, two thirds of the 22.9 million people are under 18 and most of them never leave their village. I don’t know about other areas, but in the Ranomafana region, there are two secondary schools among all 130 villages, and they’re both private. This means that most kids grow up without learning anything about where they live or what they can do to take care of their community and themselves. To me, this seems to be a serious problem.

What role does PLAY have in the picture?

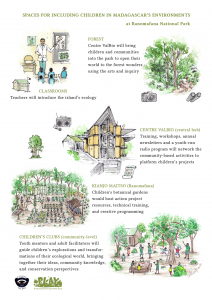

The idea of PLAY is to support those in Madagascar in working towards improving pathways for including rural lives.

This means revisiting relationships between parks, people and learning to address the roots of social exclusion, whether through social research, human development, or learning infrastructure.

What were some of your big takeaways from your most recent year in Madagascar?

The biggest thing is that it’s not really about any one of us. Nothing I do really means anything unless it’s what the people there want to see and it’s done in a way Madagascar can get behind

There are a lot of experienced social leaders in Madagascar from Madagascar who share these concerns about rural inclusion and learning; it’s inspiring to keep meeting more talented, passionate, caring people, all working towards the island’s future.

It’s made me realize that these ideas have really ever been mine. I’m trying to be a better listener – to hear what those in Madagascar see as the challenges and support doing something with those ideas. I have an ability to connect these people and places, and that’s all I can do to further hope as an ally to the island.

It sounds like you’re committed to including and collaborating with the communities your project would impact.

Are there any challenges you encounter from keeping this central part to your mission?

Yes, everything relies on partnership. The effectiveness of those partnerships depends on recognition of who offers what when and where.

Whether the organizations see the value in local people’s perspectives or whether they feel these people have knowledge that is worth including in the process of trying to change things, makes a big difference, but also can be mobilized. Part of the challenge is finding an entry point to enter new ways of working together.

Local people need to feel that their knowledge is valuable. Nobody will follow through on projects if they’re told that everything they’ve known about their own life is wrong, and that they’re destroying biodiversity.

That sense of shame and fear and powerlessness is too strong and can overwhelm the energy that is involved in being part of a dynamic process, like sustainable development. Sustainable development is not a “one stop shop”, especially in Madagascar. There has never been one solution that solves everything so if it’s not a smooth process of exchange and people aren’t involved in adapting different ideas to work for them, then, it’s just not going to work.

What is your inspiration? What drives you and keeps you going?

There’s this energy in Madagascar and to me that is such an exciting, hopeful thing. Just realizing that there’s all this active energy that just needs the chance to jump in, feels like the best bet for conservation and sustainable development.

It’s apparent that there are a lot of great people capable of doing a lot of great things. I’m inspired that these people exist, that they care, and that many would do more, if given the opportunity. Those channels just need to be created.

Ultimately, why Madagascar?

Madagascar is an extreme case of many complex issues coming together. Yet, it’s exciting in the way that every species and every landscape is so bizarre and different and interesting and there is so much to be learned from Madagascar.

But because it is so different…it’s so unique…it also is so vulnerable to change. Madagascar is a case study in how the issues that effect people all over the world intersect with the issues that affect wildlife and environments. If these two different types of problems are not addressed in a unified way, both human populations and wildlife are going to be in trouble.

When you’re in Madagascar, you meet people who care so much about their magical home, but aren’t included in it! You want to root for them. You want these things that come together to work out.