In this post, we learn from Susan Lawrance and Dr. Giuseppe Donati about their recent research on the impact of Covid-19 on conservation projects in Madagascar.

- Susan Lawrance is from the UK and has just completed an MSc in Primate Conservation. She would like to thank LCN members for giving their time to participate in this study.

- Dr Giuseppe Donati is a Reader in Primatology. Over the last twenty years he has conducted research on behaviour, ecology, and conservation of lemurs and New World monkeys, and produced numerous publications in peer-reviewed journals or books.

What was the main purpose of the research?

The purpose of this study was to find out how resilient organisations involved in conservation in Madagascar have been during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.

Here we chose to define resilience as ‘an organisation’s ability to survive, adapt, recover and thrive in the face of unexpected and catastrophic events in turbulent environments’ (Chen et al., 2021).

We used the findings from an online survey to examine the extent to which conservation projects were paused, measuring the impact on income, reviewing business operations and identifying implications for wildlife protection. The aim was to provide recommendations for post-pandemic conservation and development recovery strategies. Twenty-five organisations (global and national), many of which are members of Lemur Conservation Network contributed to the survey.

Why undertake this research?

In Madagascar, conservation has to address many issues against a backdrop of challenges such as food insecurity, weak governance, and poor infrastructure.

NGOs are under pressure to raise funds that both support lemur conservation and sustainable livelihoods within the communities around protected areas. The pandemic has made it clear that sources of funding, such as from ecotourism, that contributed to activities, can be unreliable and short-term.

In fact, Madagascar is reported to have lost around US$132 million in tourism revenue year on year to March 2021 (World Tourism Organization, 2021). As Malagasy tourism is mainly wildlife-based, the impact has been severely felt in the conservation sector not only through a direct funding deficit but also through increased human-wildlife conflict, environmental degradation and reduced research and monitoring to support long-term conservation goals (Chowdhury et al., 2021).

This study examines the extent of the impact and sought to uncover opportunities for organisations to develop recovery strategies to build future resilience.

What were the main challenges faced by organisations because of Covid-19?

Calculations analysing the status of conservation projects in the different protected areas showed that Net Conservation Value was reduced by nearly a third due to the number of projects reported as being paused.

The negative impact was particularly high in Andasibe Mantadia National Park, Betampona Special Reserve, Ranomafana National Park, the Fandriana Vondrozo Midongy forest corridor (COFAV) and the Sofia region in northwest Madagascar. As 59% of organisations cited reduced revenue as the biggest operational challenge, the loss of ecotourism revenue may have caused the high impact in these areas but further investigation is recommended so that appropriate action can be taken.

The study looked into whether the organisation profile had an impact on the extent of disruption. It was found that operational changes were not influenced by size of organisation but there was a difference in the type of operations impacted between large and small organisations.

Large organisations most often reported having to temporarily close offices and operate online where possible, due to the travel ban affecting international staff. Small organisations reported having to pause projects more often, due to fewer staff available to run them.

What were the positive findings from the research?

Continued Business Operations

It is encouraging that despite extremely challenging circumstances, some business operations have continued. Disruption to ‘business as usual’ presented an opportunity to review and improve operations, such as capacity-building using local employment, and increased use of technology, such as website development and online meetings.

‘‘Due to the pandemic, we have re-oriented our business from ecotourism towards biodiversity conservation and the sustainable co-management of natural resources to protect our heritage and facilitate economic recovery as soon as tourism resumes.’’ — Small Malagasy organisation

Resiliency

Organisations were asked to score on a scale of 1-10, (1-low, 10-high), how resilient they thought they had been during the pandemic. Just over half (55%) of large organisations (greater than or equal to 50 staff in Madagascar) reported a score of 7 or above, whilst 68% of small organisations (less than 50 staff) reported a score of 7 or above, with nearly 40% reporting 9 or 10. This optimism was perhaps due to the increased involvement of local people with making COVID-19 safety equipment, undertaking health and hygiene awareness training and wildlife patrolling.

Community Employment

Where the organisation was a community employer, fewer community income-generating projects were paused. With 88% of organisations reporting they were community employers, this appears to be ahead of other African countries where, in one study, local employment was rated of average importance in a list of conservation operations (Waithaka, 2021a). In terms of wildlife monitoring, 50% of organisations said they were able to continue with the same level of protection, while 50% indicated there had been a level of compromise such as reducing the area protected but there was still some protection in place.

“With many NGOs relying almost entirely on ecotourism, we have focused on empowering people to help themselves — and ultimately find a balance between humans and nature……….By creating a holistic program that does not ONLY focus on research or ecotourism, we were able to continue conservation — despite the pandemic…’’ — Small international NGO

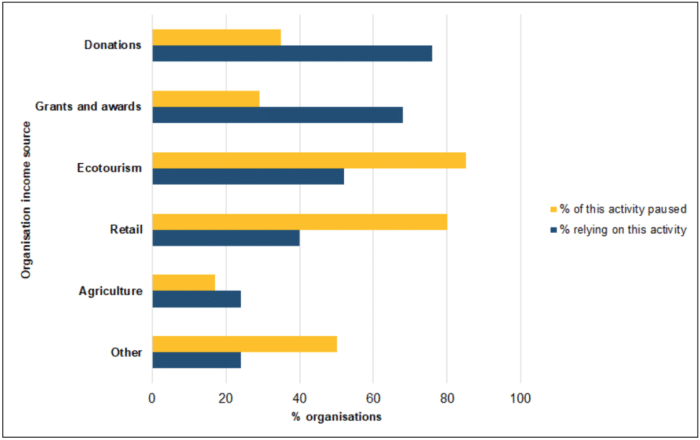

Whilst there maybe an over-reliance on ecotourism as a funding source globally (Attah, 2021), Madagascar appears to be in a better position with only 52% of organisations reporting they relied on revenue from tourism-related industries, with most applying a wide range of income-generating sources. Organisations which had received additional funding to mitigate the effects of the pandemic (just over 52%) perceived themselves to be more resilient. Sixty-eight percent of organisations relied upon donations and over 65% reported that these continued to be provided during the pandemic (Figure 1.).

What could organisations consider as part of their recovery strategies from Covid-19?

Although reporting resilience and resourcefulness in this study, organisations were also extremely challenged by the pandemic.

In order to withstand future shocks, organisations could therefore consider the following:

- Develop crisis management plans in collaboration with local communities to develop strategies that involve in-country research, training, and management.

- Continue to increase the scope of community involvement in conservation. This could include employment, training and knowledge exchange.

- Expand conservation education strategies to link the health of biodiversity to human health. This would include prioritising collaboration with communities to increase awareness of the transfer of zoonotic diseases and to develop sustainable livelihoods that benefit both human health and the environment.

- Quantify the Net Conservation Impact by protected area to include a financial value that can be used to bid for further post-pandemic funding. Identify why smaller protected areas appeared to be highly affected and how resilience can be improved.

- Quantify involvement in the humanitarian effort, particularly in the south of Madagascar, and use the findings to leverage additional funding from the government and the health sector to progress the One Health agenda.

- Ensure that income-generating opportunities are diversified. This could include seeking out revenue sources from within Madagascar and ensuring that post pandemic ecotourism both contributes directly to the protection and conservation of wildlife and supports sustainable livelihoods.

- Increase the knowledge network among NGOs operating in Madagascar. This study has found that challenges were similar regardless of the size, location or type of organisation, and that resilience and entrepreneurial spirit were evident across most organisations. Collaboration to increase knowledge and share of voice at a local and national level is clearly beneficial.

References

- Attah, A. N. (2021) ‘Initial Assessment of the Impact of COVID-19 on Sustainable Forest Management – African States’: United Nations Forum on Forests. Available at: https://www.un.org/esa/forests/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Covid-19-SFM-impact Africa.pdf (Accessed: 23/02/21).

- Chen, R., Xie, Y. and Liu, Y. (2021) ‘Defining, Conceptualizing, and Measuring Organizational Resilience: A Multiple Case Study’, Sustainability, 13(5), pp. 2517.

- Chowdhury, R. B., et al. (2021) ‘Environmental externalities of the COVID-19 lockdown: Insights for sustainability planning in the Anthropocene’, Science of The Total Environment, 783, 147015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147015.

- Waithaka, J. et al. (2021b) ‘Impacts Of Covid-19 On Protected And Conserved Areas: A Global Overview And Regional Perspectives’, Parks Journal, 27 (Special Issue). doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2021.PARKS-27-SIJW.en.

- World Tourism Organisation (2021) International Tourism And Covid-19. Available at: https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-and-covid-19 (Accessed: 29/06/21).