Recently, I had the opportunity to visit the Lemur Conservation Foundation’s lemur reserve in Myakka City, Florida. LCF’s Zoological Manager Caitlin Kenney spoke with me about their work at the reserve and in Madagascar, and introduced me to their seriously adorable—and cheeky—lemurs. In this blog post, I’ll share photos of the reserve and the lemurs it houses, discuss LCF’s history, and explain how this reserve is helping to preserve these endangered primates.

In a later blog post, I speak with LCF’s Madagascar Director Erik Patel to discuss LCF’s conservation successes in Madagascar.

About the Reserve

LCF’s Myakka City Reserve is in the middle of rural Florida, and not open to the general public, except on their annual community day in the fall. Though they are not set up as a zoo for visitors, they are accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) as a Certified Related Facility, and are active participants in the Species Survival Plans (SSP) for the lemur species they house.

LCF’s reserve has two large, 10 acre forests, with hopes to split one of them into two in order to house more free-ranging lemurs in the next couple of years. The forests existed when the property was bought in 1997, so they have naturally growing Floridian trees. These types of trees work better in the Toomey forest, where low branches offer plenty of lemur pathways. In the North forest, the trees lack the same connectedness, so LCF has added an impressive network of ropes that the lemurs are happy traversing, as well as a large patch of bamboo that the mongoose lemurs love to hang out in (and hide from my camera!).

The Lemurs at LCF

In all, LCF cares for 49 lemurs of six different species, with many of them living in the forest. While ideally they would all be living in the forest, some of the lemurs are not well-suited for it, so they are kept in one of two buildings with large indoor and outdoor areas, with plenty of enrichment and attention.

Safeguarding Lemurs through the Species Survival Plan

In the past, some of their lemurs were rescued pets, but now, many of the lemurs were born at LCF, or acquired from zoos or other facilities through the SSP or Prosimian Taxon Advisory Group (PTAG) for breeding purposes. This helps keep genetic diversity among the international captive lemur population as a safeguard for the species.

In fact, the Lemur Conservation Foundation has the last male Sanford brown lemur in captivity, named Ikoto! He is about 22 years old (very old for his species). He does not have a mate, but he does have a brown lemur he pals around with. These guys are too fragile to be forest lemurs; they are happier, more comfortable, and safer in their enclosures.

Participating in the Photo Ark Exhibit

Ikoto became a star when he was photographed by Joel Sartore for National Geographic’s Photo Ark project. Zoological Manager Caitlin Kenney tells me it was quite a feat to get this little lemur photographed! It took five people to help with the photo tent to ensure Mr. Sartore got some great images!

About his Photo Ark project, Joel Sartore says, “For many of Earth’s creatures, time is running out. Half of the world’s plant and animal species will soon be threatened with extinction. The goal of the Photo Ark is to document biodiversity, show what’s at stake and to get people to care while there’s still time.”

» Check out the Photo Ark images of Ikoto!

» Buy prints from the Photo Ark project to help Joel Sartore continue the project

LCF’s Forest Lemurs

Each forest is home to three family units of lemurs: ring-tailed lemurs, red ruffed lemurs, and mongoose lemurs. The forest lemurs roam free, with access to an open enclosure for food and protection from the weather and predators like large birds. While they can travel to any part of their large forests, the different groups tend to stay in the same general areas, often spending time in the trees surrounding their enclosures.

During my visit, I saw the red ruffed lemurs in the Toomey forest traversing the tall trees, and the ring-tailed lemurs hopping around their enclosure and the area surrounding it.

The ring-tailed lemurs were so full of antics: incredibly mischievous and cheeky! The Toomey forest ring-tails were running around in play, rolling on the floor and hopping at each other. So full of energy! In the North forest, the mongoose lemurs and ring-tailed lemurs came scurrying down their rope paths to greet us. These ringtails and mongoose lemurs were very focused on making sure I got great photographs of them, posing very obviously for the lens. Such show-offs.

Interestingly, each forest has its own social hierarchy, and it isn’t necessarily what you would expect. In the Toomey forest, the ring-tailed lemurs are at the top of the social structure despite their small size, and the mongoose and red-ruffed lemurs are in a bit of a tie for second place. In the North forest, the red ruffed lemurs are at the top of the structure (which makes more sense since they are larger!). Here, the ring-tailed lemurs are in the middle, and the mongoose lemurs are at the bottom.

Conservation Education Projects

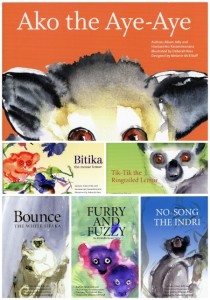

In addition to LCF’s work participating in Species Survival Plans, an important part of their mission is education and art, which come together perfectly in the Ako Project, which were written by the late Dr. Allison Jolly, and translated to Malagasy by Dr. Hanta Rasamimanana. Accompanying the books are educational posters for classroom and home school use.

In order to help spread this message of education and ensure that this amazing book series is put to good use, LCF trains teachers and gives them resources to help them teach the material. Currently, they are working on a series of 140 lesson plans to help teachers integrate the books and their stories of lemurs and Madagascar into their curriculum (the lesson plans will be available in both English and Malagasy).

How the Lemur Conservation Foundation Began

The story of LCF’s beginning is the perfect story of turning inspiration into action.

Founder Penelope Bodry-Sanders was an actress and singer on and off Broadway in New York, a Dominican nun, and author of the well-received book African Obsession: The Life and Legacy of Carl Akeley. She worked as an education coordinator at New York’s American Museum of Natural History for over 18 years, and in that role, arranged trips to Madagascar with Dr. Ian Tattersall.

Penelope was so inspired by her visit to Madagascar that she knew she needed to do something to help.

When her friend and neighbor passed away and she received a substantial inheritance, she decided to start a reserve to help protect lemurs from extinction. She dropped her career at the Museum of Natural History, and went all-in for lemurs in 1996. She picked Florida because the climate is similar to lemur’s natural home in Madagascar, and searched for a large forested piece of land to purchase.

She got lucky, and got the land for a steal. The previous owners were in trouble with the law and needed to get rid of the property—and fast! Good luck for the lemurs! She snagged the land, and lived on it in a safari tent until proper buildings were constructed.

LCF received their first eleven lemurs a year later in 1997, on loan from the Duke Lemur Center as a trial run. Penelope and her team proved their value and credibility as a reserve, and received their certification from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums soon after. Now, twenty years after their initial founding, their reserve is at capacity with 49 lemurs, they play an important role in the Species Survival Plan, and make significant contributions to conservation in Madagascar. Almost all of their funding comes from private donations, so your contribution can make a real difference.

Stay tuned for a second blog post about LCF’s work in Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve, Madagascar!