In a recent post, we chatted with Zoological Manager Caitlin Kenney about the Lemur Conservation Foundation’s work in the United States at their lemur reserve in Florida.

In a recent post, we chatted with Zoological Manager Caitlin Kenney about the Lemur Conservation Foundation’s work in the United States at their lemur reserve in Florida.

Today, we talk with Dr. Erik Patel, LCF’s Conservation Program Director, about LCF’s work protecting the Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve (ASSR) in the SAVA region of northeastern Madagascar. We’ll be discussing what makes ASSR unique, why it needs to be protected, and the Lemur Conservation Foundation’s work in this region.

About Dr. Erik Patel

Dr. Patel is the Conservation Program Director of Lemur Conservation Foundation. He has been working in Madagascar every year since 2000, where he has been studying the behavioral biology and conservation of one of the most critically endangered primates in the world, the silky sifaka lemur (Propithecus candidus).

He also serves as the Madagascar country field representative for the international environmental organization Seacology and as a member of the Madagascar Primate Specialist Group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Previously, Dr. Patel served for several years as Project Director of Duke Lemur Center’s SAVA Conservation Project.

His fieldwork has garnered considerable media attention, including several televised feature films (by the BBC, Dan Rather Reports, Animal Planet) as well as newspaper/magazine coverage. In April 2010 his “Saving the ‘Ghosts’ of Madagascar” made the cover of Smithsonian Magazine.

About the success of his work in this region of Madagascar, Erik says,

The conservation success we are finally having now is due to several factors: 1) The end of the political crisis in 2014, 2) the fact that I have been returning to this region each and every year for the last 15 years; working deep in several protected areas as well as in rural villages, and 3) the support of extremely knowledgeable local guides from Marojejy National Park. By always consulting these local experts and local communities before establishing new projects, we are better able to choose sustainable projects which will benefit lemurs and rural forest bordering communities.

A Brief Lesson on the Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve and the SAVA Region

The SAVA region is the third largest rainforested landscape in Madagascar, making it a critical area for habitat and species protection. There are three distinct protected areas in this region:

- COMATSA (2,453 square km)

- Marojejy National Park (556 square km)

- Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve – ASSR (279 square km)

Both Marojejy and ASSR are managed by Madagascar National Parks (MNP), and COMATSA is managed by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

ASSR has been a protected area since 1958. While it is well managed by MNP, until recently, it had absolutely no infrastructure (like running water, building structures, or good road access). This made it a very difficult destination for scientists and tourists, and in fact, the area saw only 20 visitors in 2014.

With an abundance of unexplored land and amazing biodiversity, ASSR has huge potential for scientific exploration and travelers!

What makes ASSR so special?

Large Elevation Range = Tons of Biodiversity

ASSR spans 2,064 vertical meters (that’s 6,772 feet!) with four elevation zones. Because of this large elevational range, there is a tremendous amount of biodiversity, and many species exist nowhere else in Madagascar (or the world). Much of the area remains undiscovered, and there is potential for even more unique species to be found if more research is done.

The classic biological inventory conducted by Dr. Steve Goodman and colleagues in 1994 identified at least 94 species of birds, 93 reptile and amphibian species, 180 ants, 211 ferns, and 12 species of lemurs. The Madagascar Red Owl was thought to be extinct before rediscovery in ASSR in 1993. And, one plant species, Takhtajania perrieri, is so ancient that it was around when dinosaurs roamed the earth!

At Least 12 Species of Lemur Live in ASSR, including the Critically Endangered Silky Sifaka and Indri.

ASSR is also home to at least 12 types of lemur! ASSR is the ONLY protected area where silky sifakas and indri both live and regularly encounter one another (i.e. they live sympatrically), and the indris here are uniquely all black (most indris are black and white). Most of the lemurs species in ASSR are not found in captivity, and research has shown that both silky sifakas and indri may not survive in zoo settings.

In addition to the critically endangered silky sifaka and all-black indri, one can also find the White-fronted brown lemur, Aye-aye, Mittermeier’s mouse lemur, Hairy-eared dwarf lemur, Red-bellied lemur, Northern bamboo lemur, Seal’s sportive lemur, Eastern woolly lemur, and the Greater dwarf lemur.

Protecting silky sifakas and indri in the wild is our only hope of saving them from extinction and preserving them for generations to come. These rare species need our help, and LCF is the only Lemur Network member working to protect them in ASSR.

What makes Silky Sifakas so unique?

- They live in the highest elevations of any sifaka species, preferring areas over 650 meters of elevation. They even live in mountainous areas as high as 1900 meters, where it can be extremely cold in the winter.

- They are one of the two or three largest lemurs in Madagascar.

- While early explorers believed they were albinos, this is not true. In fact, their skin depigments rapidly with age, perhaps more than other primate in the world. All individuals are born with black faces, and lose their skin pigment all over their body (not just the face) as they age.

How rare are Silky Sifakas?

They are one of the rarest animals in the world with less than 2000 individuals remaining.

In a 2016 issue of Madagascar Conservation and Development, Patel explains recent population density estimates of silky sifakas in ASSR. This research shows the density of silky sifakas is “considerably lower than most other eastern sifakas” and even lower compared to sifakas in western Madagascar. Silkies number from .29 individuals per km² to 2.59 individuals per km² (depending on the area of ASSR), while eastern sifakas like Milne-Edwards and Diademed sifakas number ~4.73 indiv./km² and ~7.3 indiv./km² respectively (according to data from Wright et al., 2012 and Irwin 2008). Silkies are more similar in density to the extremely rare Perrier’s Sifaka, whose density is ~3.1 indiv./km², (Banks et al. 2007).

Compared to sifakas living in western Madagascar, the difference is even greater. Golden-crowned sifakas number about 34 to 90 indiv./km² (Quéméré et al. 2010); Coquerel’s sifakas range from 5 to 93 indiv./km² (Kun-Rodrigues et al. 2014); crowned sifakas range from 49 to 309 indiv./km² (Sal- mona et al. 2013); and Verreaux sifakas range from 41 to 1036 indiv./km² (Norscia and Palagi 2008).

As you can see, silky sifakas are quite rare indeed.

What Conservation Threats does ASSR Face?

First and foremost, Madagascar National Parks receives very little funding from the Madagascar government to protect this reserve. While the reserve has strong local partners, there is not enough funding to adequately protect the land. In fact, there are only 5 park rangers for the entire 279 square kilometers (that’s 108 square miles)!

With the human population around the park growing, there are not enough resources for neighboring communities to live in concert with the natural areas without harming the ecosystem. Additional threats are faced by a main road that crosses the park on its way to western Madagascar, resulting in heavy foot traffic, artisanal mining, and bushmeat hunting along the road. While there currently is not much illegal rosewood and ebony logging in this area, its proximity to the heavily logged Marojejy National Park is a real concern.

Without larger financial resources, stronger community development, and increased park management, ASSR and its biodiversity are at risk.

What is the Lemur Conservation Foundation doing to address these conservation issues and protect ASSR?

LCF’s work in ASSR supports both the people that live near the reserve and the biodiversity within the forests.

Erik says, “It is absolutely critical that our programs both engage local communities as partners, and that communities can earn income and improve their livelihoods through conservation activities.”

Supporting Communities in Nearby Villages by Ensuring Community Buy-In and Hiring Local Staff

LCF has successfully secured a collaboration agreement with the park director, and regularly holds meetings with community leaders to assess their needs, interest, and determine future project goals.

Additionally, LCF has hired a full-time staff member to lead the SAVA office, Mr. Louis Joxe Jaofeno, who was born and raised in the SAVA region and has a background in tourism and conservation. They work with a dozen other local staff on a project basis, as well as the Marojejy National Park guides, several local technical specialists, and Malagasy graduate student Jo Rakotoarison.

Educating Local Children and Supporting Community Health

A core of all of LCF’s work—in Madagascar and in the U.S.—is education. In the SAVA region of Madagascar, they have several educational programs at local schools, with more planned for 2016. These projects include:

- A tree nursery and reforestation program with the primary school;

- Educational forest visits with local school children;

- Educational posters in Malagasy for local schools;

- Teacher trainings in environmental education near several protected areas in Madagascar, including ASSR, conducted by leading Malagasy Primatologists such as Dr. Josia Razafindramanana and Dr. Jonah Ratsimbazafy; and

- Distribution of bilingual (Malagasy and English) books from the Ako Series (pictured right), which LCF developed in partnership with the late Dr. Alison Jolly.

LCF’s work also focuses on human health and family planning, expanding the reach of the Marie Stopes Nurses and allowing them to reach distant forest-bordering communities.

Building Infrastructure for ASSR

LCF has accomplished a lot in the past two years to add much-needed infrastructure for ASSR, in order to encourage researchers and tourists to visit the area and help solidify park boundaries.

Camp Indri

They are currently building Camp Indri, which gives visitors a home base and includes roofs for tent shelters; the “Emily Fisher” dining pavilion; running tap water; buildings for toilets, showers, and storage; and a simple trail system.

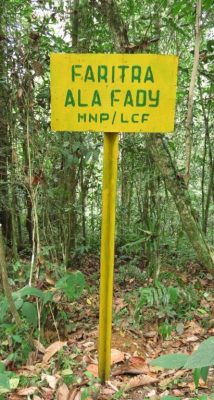

Marking and Protecting the Boundary of ASSR

In 2015, LCF completed 75% of the boundary demarcation of ASSR. 100% will be completed by July 2016, so that hundreds of boundary signs make it clear that the area is protected by Madagascar National Parks and the Lemur Conservation Foundation.

We asked Erik why boundary demarcation is so important. He responded,

Many large protected areas around the world suffer from incomplete boundary demarcation. It is important to demarcate the boundaries both to inform local communities where the actual boundary is and to prevent the reserve from shrinking in size as deforestation has often occurred in Madagascar in areas inside and adjacent to protected areas which are not fully demarcated.

In the case of ASSR, it was particularly important to demarcate the new western extension which doubled the size of the reserve and only became official in 2015. We are fortunate that we now know the exact size of ASSR and Marojejy; unfortunately that is not true of some other protected areas in Madagascar and around the world. Activities such as boundary demarcation also are another nice way for park staff and local forest police to earn money by engaging in conservation activities.

Forest Monitoring and Lemur Surveys

LCF completes forest monitoring missions with the forest police and park rangers in less visited areas of the park, in order to look for recent habitat disturbance like mining, logging, and lemur traps.

LCF has recently completed lemur surveys at four remote sites in the park, the first work of its kind in this region over 15 years. This longer term research is critical to know how many species of lemur are in the area, how many remain in each population, and if they face unforeseen threats like forest fragmentation or increased hunting.

About this work, Erik says,

If lemur traps are found, they are destroyed; if bush huts are found, they are destroyed. In some cases, small groups of miners are scared away. But we also document and GPS any encounters with lemurs. Although these short forest monitoring missions are more focused on habitat disturbance, we also engage in longer true lemur surveys (which can last 1 to 3 months per site). Of course, another benefit of both the forest monitoring surveys and the lemur surveys is that local guides and forest police and other participating local residents earn money by protecting the forest.

A Solid Foundation for Conservation

With the Lemur Conservation Foundation’s work, the Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve is on its way to becoming a viable research and tourist destination. By working closely with neighboring communities, they’ve laid the solid foundation needed to protect this land and its abundant wildlife. But, there is still a lot of work to be done.

How Can You Help LCF Protect ASSR and Its Biodiversity?

The more funding LCF has, the more they can do to protect this precious lemur habitat. The majority of LCF’s funding comes from individual donors like you, so your donation can make a real difference!

- Donate to LCF (Donations can be earmarked for Madagascar programs.)

- Use this PowerPoint presentation to talk to your school, church group, or friends about the Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve (ASSR) and LCF’s work protecting lemurs in Madagascar

- Learn more about Erik Patel’s work with Silky Sifakas on his Facebook page

- Buy the Ako book series and read to your kids about lemurs

- Visit LCF’s Lemur Network profile page

- Visit LCF website

LCF’s work in ASSR is largely supported by the Nature’s Path EnviroKidz 1% for the Planet program.

LCF’s work in ASSR is largely supported by the Nature’s Path EnviroKidz 1% for the Planet program.

Purchasing EnviroKidz products helps fund LCF’s conservation education programs and work in ASSR!