First, can you describe your background and research focus?

As an African-American born and raised in California, I shouldn’t be in this field. I shouldn’t have watched NatGeo wildlife documentaries or gone camping or raised butterflies. Fortunately, I was exposed to the world of wildlife through my dad, who loved animals. But my exposure to wildlife was still limited.

I got to college (NC State) and was highly disappointed to realize that studying wildlife wasn’t just following them around in exotic locales while David Attenborough provided the voice-over narration. In fact, it was more white-tailed deer and game management.

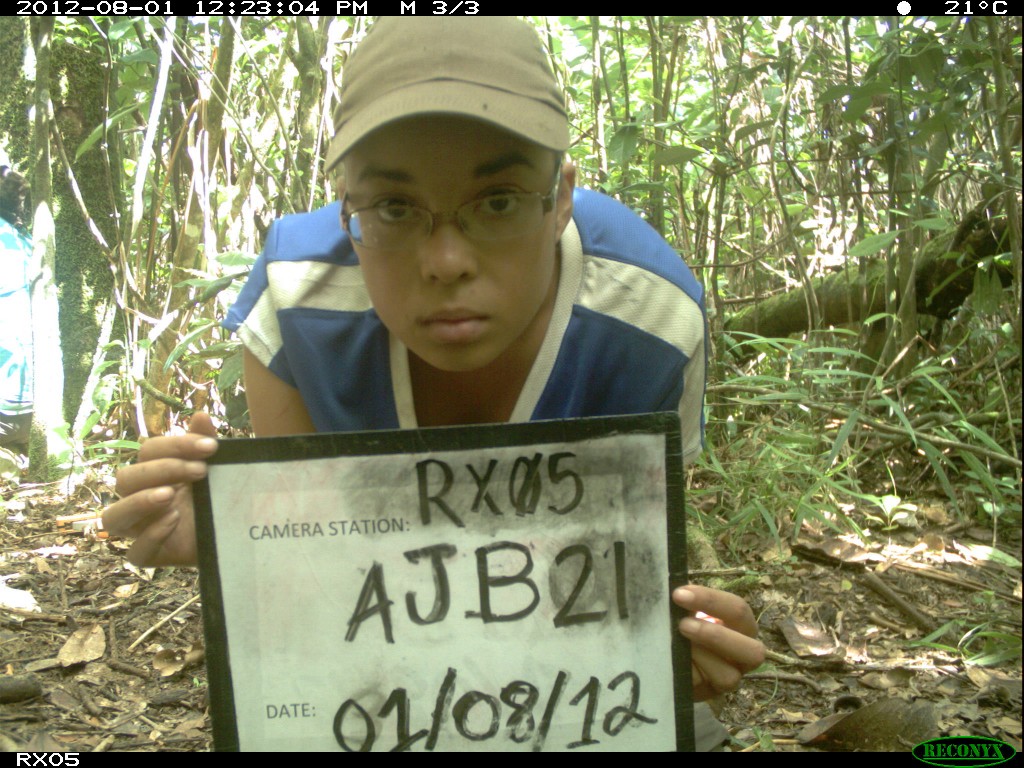

I was ready to switch over to another rather low-paying field: creative writing. It wasn’t until I finally got my hands dirty with a small mammal field project as part of a NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) that I regained my excitement about working in the wildlife field. I did another NSF-REU that got me connected to my co-adviser, Dr. Marcella Kelly, and gave me my first experience with camera trapping. After that, it’s all history.

I used to say my research focus was carnivores. What about carnivores? Anything about carnivores. Just…carnivores.

However, I’ve recently, begrudgingly, accepted that I find small mammals and birds just as interesting as the fosa (Madagascar’s largest native predator). I’ve even gotten over my prejudice against primates thanks to my graduate research having a focus on lemurs (the prejudice came from a bad experience with chimps at the Sacramento Zoo where I volunteered…don’t ask). One day, I might even find studying herps interesting! So I’ll just say my research focus is any species that is little known and living in an international, tropical country.

How did you get interested in working in Madagascar? What were your motivations?

During my initial visit to Virginia Tech, my other co-adviser, Dr. Sarah Karpanty, lured me in with the idea that I could work on a large camera trap dataset from Madagascar collected by my colleague, Dr. Zach Farris. That I might even be able to go to Madagascar to do field work and I might be able to focus on the fosa (which I didn’t know was a real animal until then).

International field work? Carnivores? Exploring a place and studying/seeing things that few had before me? That’s all I needed to hear. It seemed like the perfect project. My motivations were (and still remain, sad to say) what might be deigned as incredibly selfish.

Can you describe your work in Madagascar, what you are working on right now, and your research plans for the next year?

My past work (i.e., my graduate research) focused on using the six-year camera trap dataset from seven sites across the Masoala-Makira protected area complex to determine how ground-dwelling forest birds, small mammals and lemurs were faring in the face of habitat degradation and the presence of exotic predators, like cats and dogs. I estimated the occupancy of seven bird species, three tenrec species and the density of two lemur species (white-fronted brown lemur and eastern woolly lemur). I also followed occupancy (birds and small mammals) and encounter rate (lemur) trends over the years at two of our sites, which were resurveyed throughout the years.

The last was the most interesting of my objectives, because out of 19 species (bird, tenrec and lemur) we monitored at one site, only four didn’t show declines in occupancy or encounter rate. The other resurveyed site was similar, with nine out of 17 species showing declines.

Currently, my day job is working in a lab picking out invertebrates from intertidal core samples. But I’m also working on figuring out how to estimate fosa density, trying to get papers published, and organizing another round of field work to be conducted this fall and winter in Madagascar.

My research plans for next year involve looking at how birds and small mammals co-occur spatially with cats and dogs on the landscape and hopefully writing grants for a continuation of this project in Makira.

Can you tell me more about the new Makira National Park. What is Makira like: the terrain, the region, the animals and plants?

I heard from a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer (RPCV) who I met during my stay there that the northeast is the “armpit” of Madagascar, and I can’t really disagree with that description. It is the largest area of contiguous intact forest left in Madagascar, most of it unexplored.

I like to think that if the giant fosa is still extant, it’ll be in the forests of Makira. It rains a lot, it’s muddy and the terrain is incredibly rugged. After my 4.5 month field season in 2013, I had back pain from jumping down trails and my knees and hips had aged about ten years.

As for the plants and animals, it’s like a naturalist’s dream. The Masoala-Makira area is a biodiversity hotspot within a biodiversity hotspot (aka hotspot-ception).

In addition, there are regional endemics (such as the white-fronted brown lemur and the red-breasted coua), which are very common there. I was surprised to learn that the white-fronted brown lemur was endangered; we always saw them.

What do you see as the biggest threats facing lemurs and their habitat? How can we alleviate those threats?

Like all over Madagascar, the biggest threats to lemurs would be hunting and habitat loss/degradation.

We need to find a way to help the locals and help local biodiversity at the same time. Human livelihoods would have to be the priority.

Providing and subsidizing birth control is one small solution. Teaching about more efficient agricultural techniques is another. Integrating them into wildlife research and conservation—not just as tour guides for rich Europeans, but as scientists, field assistants, project managers—is essential.

The thing is, the Global North has had their fun, civilizing nature and bringing it to heel; now that we are comfortable and have easy access to all of our most basic needs, we have the luxury of worrying about conserving wildlife. The Malagasy, for the most part, don’t have that luxury. It’s unfair for us to reprimand them for doing what we did and profited from in the past (i.e., if you live in a glass house, don’t throw stones).

Sustainably developing Madagascar is the key to long-term biodiversity conservation.

What do you love about working in Madagascar?

It satisfies my explorer’s itch. I love that I have to go through tons of small trials and discomforts (15+ hour plane rides, mosquitos, terrestrial leeches, Malagasy-time) but that I’m rewarded with experiencing things few people get to experience. It gives me the sort of rush that I imagine old-timey naturalists and explorers must have gotten, walking through jungles and across deserts no one from their country had ever traversed.

I love the novelty. I love the discovery. I love the food.

What are the hardest parts about working in Madagascar?

Other than the psychologically scarring experience that is seeing terrestrial leeches inch their way up your muck boots in search of skin…the constant raining. I can usually take a cloudburst or two, but if it’s been a week with no sun, and I’m waking up putting on damp clothes, it’s tsy tsara.

What is the funniest or most memorable thing that has happened to you while working in Madagascar?

Most memorable: Probably when I made a rookie mistake during my first trip out there in 2012, drinking something I shouldn’t have, and ended up vomiting for about 24 hours straight.

Funniest: Finally seeing the black-and-white ruffed lemurs at one of our resurveyed sites—after two months of hearing them, and most of the field crew seeing them—following them for about half an hour, madly snapping pictures…and then realizing that my ISO was insanely high, causing all of my pictures to be hideously grainy. It wasn’t funny when it happened, or for a month afterwards, but now I can laugh about it.

In ten years, what do you hope to have accomplished relating to lemur conservation and/or Madagascar?

In ten years, I hope that this project will still be going on, but mostly (if not all) in the hands of local researchers. I hope that we are able to get the feral cats out of the forest, and that ecotourism to a few of our sites is booming.

I would hope that I would have been able to spread word about what’s happening in Madagascar to enough of the public that they can talk about these issues with all of the facts and might feel pressed to do something about it.

I always saw my future as a wildlife researcher being that of one who jumps from country to country—a year or so in Laos, two in Thailand, a couple in the Congo. But Madagascar has started to feel like a second home. So I hope I would accomplish enough fundraising that I could continue to work out there and see that on-the-ground conservation occurs and is sustainable.

It really is only through helping the Malagasy that we can help wildlife in Madagascar.

Take Action

This project (and my upcoming field work) wouldn’t have happened without the Wildlife Conservation Society, Madagascar program. They help us with logistics, they give us in-kind support, and the local scientists in Maroantsetra (all two of them) work tirelessly to help conserve wildlife in Makira.