Raymond received his Bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Queens College of The City University of New York, where he compared grooming patterns in hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas) and geladas (Theropithecus gelada) for his Senior Honors Thesis. More information about Raymond’s research can be found on his blog, The Prancing Papio, and he can be contacted via email at: Raymond.Vagell@gmail.com

When did you first get interested in working with lemurs and what motivated you to undertake this work?

I didn’t start working with lemurs until the beginning of last year (2014) when I was approached about an interesting study on color vision with the ruffed lemurs. Color vision is very important in primates; presumably, the ability to perceive red is advantageous for finding ripe fruits in ruffed lemurs as they are frugivores (fruit-eating animals).

However, ruffed lemurs are interesting because males cannot perceive red; the gene to perceive red is a sex-linked trait in ruffed lemurs and only females can inherit this gene. The inability to perceive red is commonly known as “color blindness”.

In fact, most color blind humans are also males because in humans, the ability to perceive red is also a sex linked gene. My work here in Duke Lemur Center is to investigate how ruffed lemurs perceive their world. Specifically, who can perceive red and who can’t. I was recently featured on Duke Lemur Center’s Instagram page for their “Meet the Scientist” event. Check out their page for more pictures about my research and my lemurs!

So how exactly do you test color vision in ruffed lemurs?

Broadly speaking, I test whether lemurs can perceive colors by training them to target a stimulus and then have them participate in a two choice discrimination task.

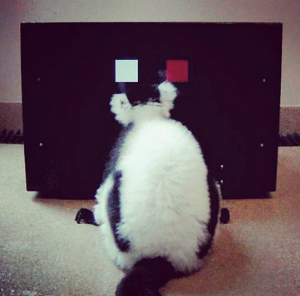

To do this, I have developed a subject-mediated automatic remote testing apparatus, aptly named SMARTA for color vision discrimination tasks. It is a machine with a touchscreen tablet that I use for discrimination tasks. When I train the lemurs to use SMARTA, I operate the machine manually but when they are doing the discrimination tasks, SMARTA runs automatically to decrease biases and reliability when collecting data. Built within SMARTA is a food delivery system that dispense food rewards.

What is a typical day like for you when you’re working with lemurs?

I usually arrive at the DLC early in the morning, around 8:30 AM. There are two reasons to this. First, the lemurs are positively reinforced with a food reward so you would want to train them before they are fed. However, you don’t want to withhold food from them too long so I generally start early and end my research around 11 AM at the latest. Just to be clear, this doesn’t mean that all of the lemurs in my study get fed after 11 AM. It’s only the last group I am working with. Secondly, I start early in the morning because I want to beat the excruciating North Carolina summer heat and humidity.

I am currently working with 3 groups, ranging from 2 to 4 lemurs. Most of these lemurs are being trained right now to station properly and to touch the stimulus we present to them except for one “star student” who “connected the dots” after being trained for 2 weeks. Her name is Halley. In comparison, some of these lemurs have been trained for over 3 months and have yet to master what we wanted them to do. So, besides training these lemurs, I am also running discrimination task with Halley.

What are the hardest parts about doing research with lemurs?

What is the funniest or most memorable thing that has happened to you while working with lemurs?

My lemurs absolutely love raisins and dried cranberries, which is why I use them as food rewards. Sometimes when I am in their enclosure, they reach out with their hands as if asking for raisins or dried cranberries (imagine a chimpanzee begging gesture!). But I guess it is memorable because with their hands outreached and staring at you, it feels like they are gazing into your soul. It’s an amazing experience and I am glad I can be part of it, almost every day.

Some of my lemurs have developed a way to “cheat the system” so to speak. They have learned a few ways to make the food reward dispense with little to no effort.

Some of them would place their hand on one side of the tablet and eventually that hand will hit the right stimulus and a food reward will drop down. Some will put their hands on the middle of the screen hoping that it will hit the correct stimulus. I think it’s funny that they have come up with ingenious ideas to get the food reward without trying to actually having to solve the task. I also have lemurs that use all their hands and feet to interact with SMARTA simultaneously.

These lemurs love SMARTA! By the end of each session, I have to move the lemurs to an adjacent enclosure and get the other lemur to come to the enclosure where I set up SMARTA. The lemurs do not want to leave! It’s like a child that can’t get enough of their video games or TV. Getting them to go to another enclosure requires a lot of positive reinforcement but sometimes they don’t even want food reward. They would rather stare at the SMARTA television screen!

In ten years, what do you hope to have accomplished in terms of your work in lemur conservation?

I hope to better understand lemur color vision and perception. I’d also like to discover more about the evolution of color vision in prosimians.

Take Action

- Raymond recommends the Duke Lemur Center as an organization that you can support!