In Andasibe, locals and transplants work together for the natural environment.

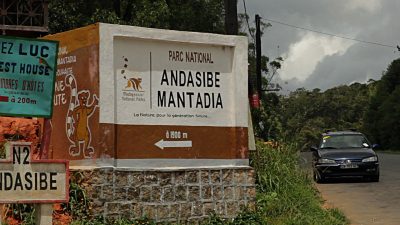

In the small village of Andasibe in eastern Madagascar, a dedicated group of individuals, both locals and transplants, are working together to halt the destruction of the natural environment. Time is not on their side. In a nation where less than ten percent of native forests remain, they must kick-start reforestation through a combination of education, conservation, and community spirit.

My husband and I set out to Madagascar with the intention of making a film about the environmental turmoil the country has been experiencing, but we did not realize that we would find our story in Andasibe, our first destination in what was to be a several month sojourn, beginning in early December of 2013.

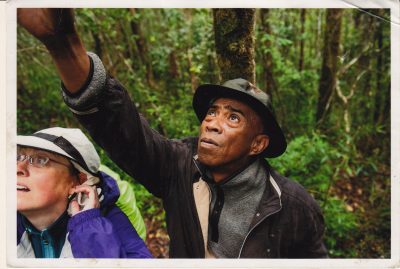

Being on a tight budget, we took the affordable transportation, via local bus, to Andasibe from Antananarivo, a bit uncomfortable, but cheap and efficient. Barely into Andasibe’s border, I guess we stood out among the locals on the bus. Claude, who would be our first guide, quickly came over to sit by us and asked if we would be interested in hiring him to visit the forest. We took him up on his offer and met him at dawn at the entrance of the national park.

The initial sensations of Madagascar’s eastern landscape can be overwhelming.

Just before daybreak, we were awakened by the chorus calls of local Indri lemurs echoing through the neighboring forest. Steps outside our door, bright green chameleons lay on low-lying branches. Lunar months lined the walkway to the hotel restaurant. And wild Sifaka lemurs hung on the nearby trees along the main route from our modest hotel to the park.

The following morning, Claude introduced us to another guide, Nirina, also a coordinator of local conservation programs. After a second day of hiking in the national park, we took a short break to enjoy lunch in the forest. Nirina nestled into a comfortable space on the damp leafy ground beneath the red-bellied lemurs that played above him. Impulsively, he began to recant folklore of man’s initial relationship with these majestic creatures. Through his storytelling, we could sense a great harmony between the Malagasy people and their natural environments.

We knew instantly that Nirina would be a great character. He had such a charismatic personality and a great devotion to encouraging his community to be more sustainable.

We decided to open the film with Nirina playing his flute along the street, hitchhiking to a neighboring community where he is hoping to start a government-sanctioned nature preserve. He explained to us that if the area became a national park, it would then be illegal for people to take natural resources from it. A group of Indri lemurs lived in the region, and he was adamant about protecting them. Turning the area into a park, he believed, was the best chance of preserving the land and the animals that inhabit it.

At the town of Ambavaniasy, he stopped to chat with a young woman, a local craft-maker, and explained, as he pointed to the surrounding deforested landscape, how the community practiced slash and burn agriculture, which, he told us, is one of the most profound threats to the area.

The Community Forest of the Sahi Organization

Being eager to meet people involved with grassroot initiatives, we asked around about community programs, and were directed to the Sahi Organization and the small patch of land they are preserving and replanting. The organizer of this community forest, the second Claude we would meet, was eager to share information about the environmental problems the local community has suffered with such as elongated dry seasons and intense cyclones. This was in large part due to the overuse of slash and burn.

Sahi’s community initiatives involve maintaining a tree nursery and trying to regrow some of the deforested land; in addition, they also teach community members about alternative methods of rice production that do not involve slash and burn, methods like using rice patties, that will be more sustainable in the long run.

We were then brought to a village on the border of the National Park. We observed the villagers go about their daily activities, many of which revolved around the distribution of rice. In the corner of a wooden house, we were brought into a discussion with village elders, a small group of aged women, who lamented government regulation of the land that traditionally belonged to their community. One day, they recalled, government officials came and forbade them from extracting resources in the forest bordering the village. Since then, they bemoaned, it has been difficult feeding their children.

This is one of the rare areas in Madagascar where the central government has forced regulation and partitioned the border of the forest to preserve as a national park.

As the film proceeds, we are introduced to Dr. Norman Uphoff, a social scientist from Cornell University, who provides us with a short cultural history of the Malagasy people and explains why they are resistant to change when it comes to their agricultural practices. Shortly after, we meet Dr. Patricia Wright, a primatologist from Stony Brook University, who has long-standing ties with Madagascar. She provides us with a discussion on the unique flora and fauna of the country and a background on lemurs and how they are currently threatened. We then meet Dr. Hal Needham from Louisiana State University who explains why biological hotspots such as Madagascar are important to overall global weather patterns.

Later, we are brought back to Claude and the Sahi Organization, walking to a spot in a shrubby wooded area, each carrying a tree seedling. We watch them plant the mini trees and listen to Claude explain how the area has been cleared of invasive plants, which must be completed before the seedlings are planted. He then explains how they are in the midst of a secondary forest, which the Sahi organization is re-growing. The primary forest had been destroyed by the community via slash and burn. Looking away into the distance, he forlornly admits, the previous round of seedlings have died because of the elongated dry season.

Smoke rises up in the distance in the midst of wooded hills.

We are brought in closer to find a woman clandestinely making charcoal. She explains the process and how long the wood must burn for.

Afterwards, we meet Dr. Meredith Gore, a professor of conservation criminology, who is there to work with Malagasy people on developing alternative livelihoods. She explains charcoal production is common practice, though it is illegal to harvest wood from native trees. She also explains there are many activities the Malagasy people rely on for survival that are against the law, though little is done to enforce it.

The film captures natural beauty, the Malagasy culture, and a biodiversity hotspot on the verge of extinction.

During the film, we experience the blended narrative of the aesthetic and the intellectual, the fable and the factual, the awe-inspiring and the horrific. We visit natural beauty endemic to the island that few will ever be exposed to; we see great mountains of land burning into extinction; we hear the call of the Indri; we listen to the echo of trees falling in the distance; and, periodically, we are brought into a discussion on endemism and carbon particles and biodiversity hotspots as we are forced to confront how the devastation of this natural land, so far removed from any of our lives, is affecting life on the planet overall.

The serious tone of the film shows the domino effect of poor policies in the central government of Madagascar: the government is indifferent, the people are poor and uneducated, the people rely on the forest for all types of sustenance and engage in illegal sales of rare hardwoods to support their families, the animals lose their habitats, the forest is destroyed, CO2 emissions skyrocket, a biodiversity hotspot is on the verge of extinction, global climate change intensifies.

Throughout the narrative, we are transported to a Malagasy culture reminiscent of the past as we listen to Nirina play his traditional flute, reminding us of a time when man was in tune with his natural environment. In the final scene, we follow him to the top of a tree house in his local village and listen to him reminisce about his childhood, few decades beforehand, when the land that he looks out upon was covered in native forest; listening to his stories, we vicariously ponder where the future of the human race will take us all in a universal manner.

Our intention with this film is to draw attention to the environmental problems in Madagascar.

Personally, I believe there are a lot of fantastic films and television programs about the exotic beauty and endemic species that inhabit the country, and they all seem to mention the environmental degradation, but I have not seen one that spends adequate time explaining to their audiences that the country as a whole is basically in critical condition. Yes, it’s important to celebrate the biodiversity and exotic species, but I think it’s irresponsible to so quickly gloss over the serious problems that are threatening Madagascar, serious problems that the Malagasy are experiencing in the present day.

Ideally, we intend to put it out in multiple languages, including Malagasy, and to have it shown in forums including the United Nations where it can add to the discussion about ecological intervention in developing nations. Madagascar is one of the most threatened biologically diverse hotspots in the world and is home to innumerable endemic species. The disruptions of this fragile ecosystem are leading to catastrophic consequences not only for people inhabiting the land but for global climate change as well. In addition to discussions on over-population and instability in the central government, the film also draws attention to the social consequences of conservation.

According to a sobering new analysis of remaining primary vegetation, the world’s thirty-five biodiversity hotspots, which harbor 75% of the planet’s endangered land vertebrates, are in more trouble than expected.

In all, less than 15% of natural intact vegetation is left in these hotspots, which include Madagascar, the tropical Andes, and Sundaland. “If we lose the hotspots we’ll say goodbye to over half of all species on Earth. It would be comparable to the mass-extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs,” said William Laurance, a co-author of the study in Biological Conservation with James Cook University.

The film includes commentary from various field experts and renowned scientists.

Experts include DR. CRINAN ALEXANDER from the British Royal Botanic Garden; DR. RAINER DOLCH, a Finish reforestation expert; DR. MEREDITH GORE, an American professor of conservation criminology; DR. PATRICIA WRIGHT, an American primatologist and anthropologist; DR. NORMAN UPHOFF, a renowned social scientist and agroecologist; and DR. HAL NEEDHAM, a climatologist and storm surge expert from Louisiana State University. Together, they paint a picture not only of environmental turmoil, but the relationship the Malagasy people have, and traditionally have had, with the land; in addition, there are discussions on over-population and instability in the central government.

Andasibe Community Members Protect Their Remaining Lands

Working in tandem with western commentary on the global consequences of deforestation, the film illustrates how Andasibe community members are rebuilding their forests and protecting their remaining lands, pulling their resources together and uniting their ideas to make conservation the economic foundation of their future. This, hopefully, can serve as inspiration to all global communities suffering with the consequences of environmental degradation.

As Nirina walks through depleted forest paths, we hear him pondering the fate of the remaining Malagasy rainforests; Claude sits beside a women’s group he is helping to unionize as we listen to them explain how there is little chance for economic survival without causing environmental harm. We hear from renowned scientists, discussing how Madagascar is home to thousands of endemic species, yet is one of the most threatened biologically diverse hotspots in the world. We also hear from Malagasy residents about the dire need to support their families and the effect that regulation has had on their ability to feed themselves.

Throughout the film, we experience the struggle between the long-term environmental needs of the country verses the very real present day needs of individuals living in it.

This is a serious conundrum, and the Malagasy people have a long road ahead of them. They must determine how to cope with the demands of a growing population while rethinking their traditional methods of survival if there is to be hope of a future with any type of stability.

Film Website Educational Resources

Take Action!

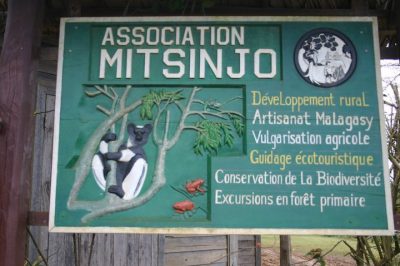

To directly support conservation efforts in Andasibe, we can vouch for donations given directly to Association Mitsinjo: http://www.amphibianark.org/donation-for-mitsinjo-project/. Please tell them that their friends at Eyes of the World Films sent you.

We would consider a donation to them as a success for our film (or you could give to both of us to help us get the word out on other important organizations).